Vuillard…At The Revue Blanche…1901…Guggenheim Museum New York

As Thanksgiving approaches, A Swift Current changes direction.

I have long hoped to share others’ memories and reflections, and now, for the first time, I am honored to share the writing of Gerry Sell.

Gerry Sell is a retired Mathematics teacher, and currently a resident of The Waters at 50th in Minneapolis. A participant in The Waters’ Writers Group, her essay Thanksgiving was originally published in Cardboard in Our Shoes, an Anthology of Reminiscences. The Writer’s Group meets twice a month, and over time their instructor Kathleen Novak observed that the group’s writings “…more and more centered around childhood and young adult memories during the tumultuous years of the Great Depression and World War II.” In the anthology, Novak writes, “they’ve culled the best for friends and family and all others who love a good story told with an honest voice…”

Here is one of those stories.

Thanksgiving by Gerry Sell

The note was on the table when I got home that night. “Mom, call this doctor at this number tonight! (underlined) Urgent! (underlined twice)”

I looked at the clock. It was after 11 PM. I looked at the name. I did not recognize it. The area code for the number was Chicago. I didn’t know anyone in Chicago. Why was a doctor from Chicago calling me? All kinds of thoughts ran through my mind. Did one of my Milwaukee relatives go there, get sick, and give my name as the contact? Was it someone calling from the university who got sick there?

I kept repeating the name. I didn’t know anyone by that name, yet I felt I should. I dialed the number. A woman answered. “I have a message to call this number,” I said.

“Oh I am so glad you called. I’ll get him. Please don’t hang up. He’ll be right here.” Now it was even more mysterious and the name kept gnawing at the back of my mind.

I heard the phone being picked up. “Hello Gerry. It’s Manuel. You remember me?” The voice was seductive, the pronunciation accented.

“No, I don’t think so.” I replied.

“Come on, Gerry. You have to remember.”

“I’m trying.” I said.

“Come on, Gerry. Think back along time ago.”

“I’m sorry,” I said again. Nothing was clicking.

“Think back a long, long time ago. “

“I’m trying.”

“Come on, Gerry. Don’t you remember? I was the skinny kid in the corner!” And, then, I did remember—yes, Manuel! He was indeed the skinny kid in the corner of one of my first college classes.

It was my first semester at Marquette, 1951. The class was zoology. The professor was an old man who was the department chair and who had written the textbook. He lectured by reading from the book, never looking up except to take roll.

We were all having trouble in that class. Not only were the lectures a waste of time, but the grad study for the lab was not a zoologist and had trouble distinguishing between male and female frogs.

The skinny kid in the corner was having more trouble than the rest of us. He was all of 5’4” and maybe 100-pounds. His English was reasonable, but he was struggling. One thing that he did know, as did the rest of us, was that without an “A” in that zoology class, there was no chance that he would be admitted into medical school.

Back then, there were no MCATS entrance exams. One did three years of pre-med, and based on grades in science classes and professors’ recommendations, one was admitted. Unless one was female. All scholarship money was reserved for MALE students.

His accented pronunciation interested me. I found out that he was from Belize. He worked on campus to pay his dorm fees. There were other students from Belize, but he was the only pre-med student and zoology threatened to make him a non-pre-med.

Another complication was that all scholarship students had to maintain a 3.5 GPA or they lost their scholarships. Manuel had to get an A in zoology for his GPA, because he was not getting an A in English.

I towered over him. Before I ever heard of “spinal compression”, I was 5’9”. My troubles were not academic but economic. I kept my coat on in class because I was still wearing my high school uniform. That didn’t matter to Manuel.

One day he very shyly asked if I would help him. So we started working together, sometimes a few minutes and sometimes two to three hours.

The day of the final exam, he looked so apprehensive. The exams were passed out and I saw him write at the top of the paper “AMDG,” Ad marjorem Dei gloriam—for the greater glory of God, which is the Jesuit motto.

I was the first person finished. I turned in my paper and left, but I just had to wait until he came out. When he did, he took my hand and smiled and said, “I answered every one and I think correctly. Thank you.”

“Good luck,” I said then asked, “Are you going home for the summer?”

“No, I cannot. I know I will have trouble in chemistry.”

The following year we were in different classes, but I saw him some. He had studied hard all summer and the textbooks were better.

He commented once that I wasn’t wearing my coat so much and that he hadn’t seen my blue jumper for a while. He also said he knew I was poor, but it was better to be poor here than in Central America.

At the end of my sophomore year, I had to quit school. My scholarships were for two years and my application for a third year was turned down because all the money was going to veterans. I tried to borrow one hundred dollars, but was told that the school didn’t give money to girls. They never paid it back.

I corrected papers for one of the Jesuit religion teachers, Father Maddigan. He was a Canadian who had served in WWI and reminded me of my dad. Even with his recommendation, I couldn’t get any money.

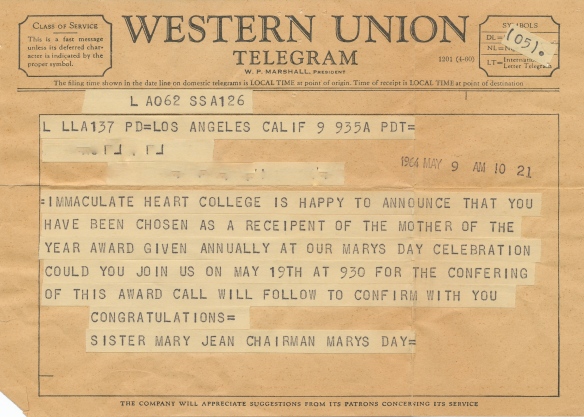

On the phone Manuel was now saying, “I got into Medical School because you helped me. And when I went to tell you, you were gone. My daughter graduated from Marquette and had the Alumni directory. I looked through every page until I found you.”

We had started talking about 1953 and what happened to us, how he had gotten into medical school and I was teaching first grade. He laughed. “Good it was first grade. High school juniors were older than you.” We talked about how each of us had married and had children. He took a deep breath. “Gerry, I want to ask you something. Please don’t be offended. Your husband, he is a good man?”

“Yes, he is.”

“In the directory, it says he graduated Summa Cum Laude.” He is also a smart man?” It was a question that was also a statement.

“Yes, Manuel. He is so smart he married me.”

“Oh Gerry, I like that and I am going to remember it. I must go now. I want you to understand what I am saying. I am what I am because of your help. Without that A in zoology, I would not have been in medical school, and I would not be a doctor. It is 50 years, but it is never too late to say thank you. Promise me you won’t forget me.”

Through my tears I said, “I won’t forget.”

“Thank you again, Gerry.”

Author Gerry Sell graduated from Marquette University in 1957. This is her graduation photo.

Thank you to Gerry Sell for permission to share her story on A Swift Current. All rights reserved.

Thank you also to Kathleen Novak, novelist and poet, who introduced me to her students’ writing. Their book of reminiscences is unfortunately sold out. However, Kathleen is the author of two novels published by Permanent Press: Do Not Find Me, a finalist for the 2017 Minnesota Book Award, and the recent, charming Rare Birds.

As we gather together for Thanksgiving, please remember this is a chance to share and record our stories. Once again, National Public Radio’s StoryCorps is sponsoring “The Great Thanksgiving Listen“–providing the opportunity to interview an elderly loved one using the free StoryCorps app. StoryCorps even offers suggested questions. Interviews become part of the StoryCorps Archive at the American Folk Life Center at the Library of Congress. For more information, visit

https://storycorps.org/participate/the-great-thanksgiving-listen/

Listen. Honor. Share.